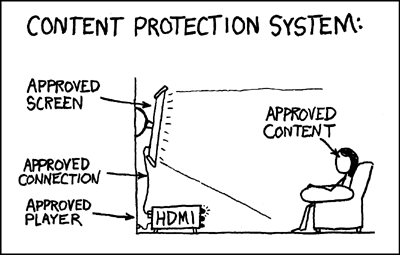

My excitement for the new Frank Ocean album was high, and it lasted until I read those three filthy little words: “Apple Music exclusive”.

My excitement for the new Frank Ocean album was high, and it lasted until I read those three filthy little words: “Apple Music exclusive”.

I’m wondering today, on an otherwise lovely Friday, how soon to introduce welfare economics into an introductory economics course.

I know. Bear with me.

I think one of the most fundamental jobs of introductory economics is to start to build the famous “invisible wall” between positive and normative economics. The textbook distinction is between questions about the way the world is—positive—and the way the world ought to be—normative.

The U.S. Justice Department today announced (NPR) that private prisons will be phased out. What a rare piece of heartening good news in the relentless weirdscape of 2016.

Olympic fever. My TV has been pretty much stuck on NBC this week (fine, NBC, I guess I see why you paid $1.23 billion for the broadcast rights!), their questionable programming choices aside. (And I certainly did NOT find… other means to watch the women’s gymnastics all-around final live today. Nope, nothing to see here.)

A brief ode to pinball, the aptest metaphor for human existence yet conceived. In which:

If you can’t get what you want, what’s the next best thing? This is pretty much the deepest question in economics, being that preferences are king in a world of scarcity.

It lives also in a more complicated way in a relatively obscure piece of economics called the theory of the second best (which stems from a paper all the way back in 1956 by Richard Lipsey and Kelvin Lancaster). I’ve been thinking about this today after going back and forth with Megan McArdle on Twitter about the funding of policy research, ending up here. The question at hand is whether “relevant” policy research is done in academia, with funding therefore from the higher education system.

One assumption, often unstated, in the economics we teach at the introductory and intermediate levels is the absence of force. Another assumption that we typically take a while to unpack is the rule of law and property rights. And still a third assumption is the cultural context of what is fair game to be traded in a society. I want to talk a little bit about where they show up in the context of two key ideas in the undergraduate-level canon, general equilibrium theory and externality theory.

As I continue my summer-long vision quest to build the platonic ideal of an Econ 101 syllabus (kidding… maybe?), I’m thinking about modeling, representation, and narrative.

The question at hand for the course is how to balance “received wisdom” versus “how we do things”. I’ve always found one of the hardest things to get across in teaching economics the idea of modeling.

From the new album Freetown Sound.

I think game theory is awesome. First of all, it is the most ingeniously named field in the history of thought. Who doesn’t want to study something called “game theory”? Marketing!

Second of all, it forces a student—it certainly forced me—to confront kinds of logic, problem-solving, and epistemological questions that are quite different to the norm. Certainly quite different to the norm elsewhere in economics, at least. It is thinking about thinking, which for a certain type of person is a fun rabbit hole.

Game theory is about how we can try to understand situations in which the outcome of my choice depends also on what you choose. These are situations with strategic interaction. I can’t just pick the thing I like best, as in the standard rational choice model. I have to think about what you want, what you might do, how you might respond, what you think about me, what you think I might do—and you have to think all of those things right back at me. It’s gnarly!

So I saw this at the Browser today:

How often do you see a reference to game theory that isn’t about the prisoner’s dilemma? Very seldom, if ever, I think, and in my opinion game theory is worse for it.

I include in that references to game theory in academic courses too, by the way. I’ve taught game theory for undergraduates many times (in the context of applications to economics), and it’s remarkable how many students come to those classes under the impression that game theory is the prisoner’s dilemma. I don’t think they are wholly to blame for the mistake.

I’m not here to tattle on anyone, but I’ve had smart students show up at game theory class and tell me that game theory is about how you should rat out your friends. Uh oh!

Now, I come not to praise the prisoner’s dilemma, but nor do I want to bury it. First, it swiftly and usefully undermines the notion that decentralized decision-making necessarily leads to mutually beneficial outcomes. Second, as with any simple game, it can be extended and varied in endless ways to tell many rich and useful stories—most obviously by thinking about a repeated prisoner’s dilemma with inducements, rewards, and punishments. Third, it’s a useful parable for a variety of real-world situations.

There are more qualities of the game, of course. For a dive into the depths of what it can teach us, I recommend its entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

But here’s the problem: the vanilla prisoner’s dilemma is the least interesting game in game theory. I’m not going to rehash the setup again here (trust me, it’s been done enough). The reason it’s the least interesting game is that the very point of the prisoner’s dilemma is that its setup gives each of the two players in the game a unilateral incentive to make a given choice.

The vanilla prisoner’s dilemma boils down to the smallest variation on the rational choice model. I don’t particularly need to think about what you might do, or what you might be thinking. No matter what you do, one of my options is always better. Yeah, it carries a non-trivial lesson, but to me it just seems so flat. I don’t really get much of a hint of the mind-bending joys of game theory from it. If this is game theory, then game theory isn’t much at all.

And so often, in my experience, students see the vanilla prisoner’s dilemma, see it called game theory, and then move on to something else. Nothing else is being imprinted on them about the example or the field. I think that’s a shame.

So in that spirit I call on those of us who would like to touch on game theory in non-game theory course, or those of us who write game theory into introductory economics texts, to consider showing, instead of or as well as the prisoner’s dilemma, some different interesting games. Here are a few of my suggestions:

I’m not saying we have to retire the prisoner’s dilemma’s number just yet. But I think we can do a little more when we give our students their first taste of the rich, fun field of game theory.

If you have any thoughts on my game suggestions, do let me know!